Marianna Cerini

Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel was one of the 20th century’s most influential couturiers. A milliner by training, she moved beyond hats to become a rebel and a trailblazer of the fashion world, creating a new sartorial style that freed women from corsets and lace frills by offering them sailor shirts and wide-leg pants instead.

“Nothing is more beautiful than freedom of the body,” she once said, and her designs lived by these words: Chanel’s silhouettes were fluid and androgynous, her designs loose and — in the case of her iconic little black dress, or LBD — democratic. She wanted women to move and breathe in her clothes, just like men did in theirs. Her work was, in many ways, a form of female emancipation.

Sunday marks 50 years since Chanel’s death, aged 87, though her legacy endures. As well as revolutionizing how we dress, she helped form a new ideal of what a fashion brand could be: an all-encompassing force that could tend to all aspects of a woman’s life, from formal attire to holiday wardrobes and evening ones.

Chanel captured her vision in “Coco-isms” that read like acerbic precursors of today’s ubiquitous inspirational quotes — “a woman who doesn’t wear perfume has no future,” or “If you’re sad, add more lipstick and attack.

“Here are 8 important style innovations from a designer who once famously said: “I don’t do fashion. I am fashion.”

Women’s trousers

Chanel didn’t invent women’s pants — they had already entered wardrobes during World War I, when women started taking jobs traditionally carried out by men. But she undeniably popularized them as a fashion garment.

The designer liked wearing pants herself (she often borrowed them from her male lovers), and, as early as 1918, began sporting flowy “beach pajamas” while vacationing on the French Riviera. Drawing inspiration from the straight, wide cuts of sailor’s pants, giving them a loose, comfortable shape, she matched them with oversized shirts or sleeveless tops.

The garment considered risqué at the time, due to pajamas’ association with the bedroom, but by the mid-1920s it become a staple among wealthy ladies and a fixture of Chanel’s collections.

Nautical tops

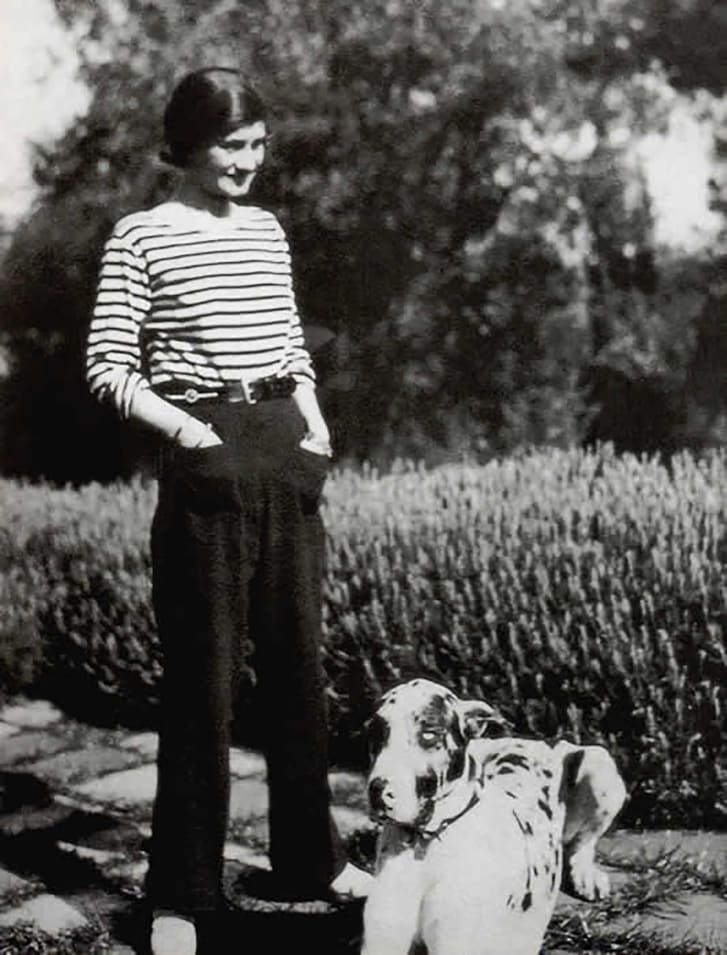

French sailors and fishermen had been sporting Breton tops — striped sweaters made from tightly knit wool to protect them from the elements — since the 19th century. Chanel, however, turned them into fashion.

Striped pieces appeared in her boutique in the society resort of Deauville, Normandy, in the 1910s. She reworked them in jersey, giving them patch pockets and accessorizing them with thick belts. The nautical look was casual, and far less serious than the stiff aesthetic of the Belle Époque, quickly becoming a hit among stylish women both on and off the beach.

Soon enough, Breton stripes could be found in the pages of both British and American Vogue. And even today, chances are you have some in your closet.

Costume jewelry

Mixing the high with the low is common practice in fashion today. But it was considered radical when Chanel introduced costume jewelry to her collections, turning something considered cheap and tacky into a symbol of modern style (though her early rival Paul Poiret should be credited with pioneering the trend).

“A woman should mix fake and real,” Chanel once declared. “The point of jewelry isn’t to make a woman look rich but to adorn her; not the same thing.”

In the early 1930s, she collaborated with Italian jeweler Duke Fulco de Verdura to create what would become her iconic Maltese Cross cuffs, adorned with multicolored semi-precious stones. By the end of that decade, she was releasing signature necklaces made of dangling, dainty chains, and intertwined with faux pearls and glittering stones. More layered strings of fake pearls followed — worn proudly by Chanel herself — and a trend was born.

The little black dress

In 1926, Vogue published a drawing of a simple, calf-length black dress fashioned from crêpe de Chine. It featured long narrow sleeves and a low waist, and was adorned with a string of pearls. The magazine described it as “Chanel’s Ford,” referring to the at-the-time wildly popular Model T. In other words, it was a garment so simple it could be accessible to any shopper — “a sort of uniform for all women of taste,” as the publication put it.

The ensemble was dubbed the “little black dress,” and the rest is history. During the Great Depression, the LBD became the outfit of choice for an entire generation of female consumers, and, in later decades, an essential part of women’s wardrobes everywhere. Countless iterations and imitations have followed, but the understated elegance of Chanel’s original number remains unmatched.

The Chanel suit

The Chanel suit was a game-changer — not just for fashion but for women’s sartorial liberation.

Coco Chanel introduced her first two-piece set in the 1920s, inspired by menswear and sportswear, as well as the suits of her then lover, the Duke of Westminster. Keen to free women from the restrictive corsets and long skirts of previous decades, Chanel crafted a slim skirt and collarless jacket made of tweed, a fabric then considered markedly unglamorous.

The suit was modern, slightly masculine in its cut, and ideal for the post-war woman making her first foray in the business world. Its popularity continued through the years, and featured across collections from the house of Chanel, including those by Karl Lagerfeld.

Some of the most influential women of all time wore the Chanel suit, too, from Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly to Brigitte Bardot and Princess Diana.

Chanel No.5

Chanel launched her eponymous No.5 perfume in 1921. A year before, so the legend goes, she had challenged French-Russian perfumer Ernest Beaux to create a scent that would make its wearer “smell like a woman, and not like a rose.” The result was a mixture of 80 natural and synthetic ingredients, which Beaux presented her with a numbered series of perfume samples to choose from.

She picked the fifth. The blend subverted the notion of fragrances as a symbol of high social class, instead pushing the idea that women could be multiple things: natural and artificial, provocative and pure.

“It was what I was waiting for,” Chanel later said. “A perfume like nothing else. A woman’s perfume, with the scent of a woman.

“It was also one of the biggest and most successful branding exercises in the history of fashion. By placing her name conspicuously on every bottle and advertisement for her perfumes, Chanel forever linked them to the house’s identity.

Jersey dresses

Chanel loved jersey. The fabric was especially prominent in her sportswear-influenced pieces, much to the shock of her clientele, which was used to satin and silk.

It was an unusual choice for the time: Jersey had, until then, been mostly used for men’s underwear.

But it was easy to work with and comfortable, encapsulating everything the designer wanted to create for her customers. Importantly for Chanel, ever the entrepreneur, it was also relatively cheap, and helped keep costs down as she established herself and her label.

She was the first designer to popularize jersey in women’s fashion, using the material for dresses, skirts, sweaters and more — a tradition Lagerfeld maintained as creative director in the decades following her death.

The 2.55 bag

One of the most iconic Chanel bags of all time, the 2.55 subverted all the rules when it launched in February 1955 (hence the name). It was the first luxury bag for women to come with a shoulder strap — earlier clutches, including those from Chanel, all needed to be carried by hand.

The groundbreaking modification offered new freedom to women, and transformed the way women’s bags were designed. Critics deemed the 2.55 uncouth, but shoppers loved its practicality. And practical it certainly was: The chain strap could double up and swing from one shoulder, a outside flap pocket was designed to store cash and the central pouch was perfectly shaped for lipstick.

The 2.55 also introduced two Chanel signatures: the deep burgundy color used in its lining, and the diamond-stitched quilting, inspired by jackets worn by men at the races.