After the Vietnam War, Annie Vang’s parents escaped persecution in Laos and traversed the Mekong River in the dead of night to seek safety in Thailand. “My family had no choice but to flee or die,” she says.

Vang and her family are Hmong, an ethnic and cultural group who lost their land—and way of life—after siding with the U.S. in the fight against Communism. Like so many other Hmong people, Vang’s family resettled in a refugee camp before coming to the U.S. in the late ’70s. Growing up in Iowa, Vang remembers being bullied for having an accent and “looking different” than everyone else. “I was told to go back to my country every day,” she says. “I just wanted to be like everyone else and assimilate and forget about my Hmong roots.”

Yet as an adult, the 44-year-old is doing everything in her power to preserve her cultural history. For more than a decade, the app developer has been digitally documenting the Hmong language with HmongPhrases, an app she created to teach the Hmong language to English speakers. “It is critical we capture this, so that our language, legacy, and stories can live on,” she says.

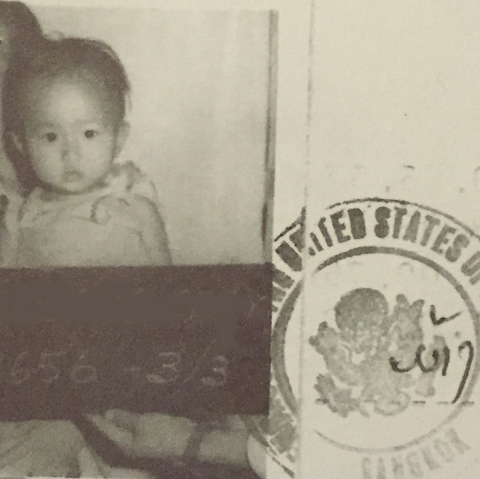

Annie’s refugee photo taken in 1978, right before her family came to the U.S. COURTESY ANNIE VANG

The Hmong people—widely considered to be one of the country’s most marginalized Asian American groups—have been in the U.S. for almost 50 years. But until gymnast Sunisa Lee competed in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, they rarely made headlines. After Lee won gold in the all-around competition, there was an uptick in interest surrounding the ethnic group, with Google reporting a spike in searches for the word “Hmong,” and the phrase,“Where are Hmong people from?”

The answer to that question is complicated. Hmong American chef Chef Yia Vang (who, like Vang, lived in a Thai refugee camp) recently told Teen Vogue that the word “Hmong” literally means, “we don’t have a land of our own.”

The Hmong people are primarily from Southeast Asia and remote areas in China. During the Vietnam War, Hmong child soldiers were recruited to fight in a CIA-sponsored operation known as the “secret war.” When the U.S. withdrew from Vietnam—essentially abandoning the ethnic group—more than 120,000 Hmongs became refugees in their own homelands, according to the Minnesota Historical Society. Many fled to Thailand, and later to the U.S., where there are now at least 18 Hmong clans sprinkled across the country—the largest in Lee’s hometown of Minneapolis-St. Paul.

While Vang doesn’t know Lee personally, she says the gymnast’s success has also put Hmong history back in the news. “A lot of people in America had never heard of Hmong before,” she says. “It makes me feel warm and fuzzy inside to read articles detailing her journey… because we all think of each other as connected in one form or other.”

When Vang’s own family came to the U.S., they settled in Pella, a small town in Iowa southeast of Des Moines. Her father, Seng Fong, got a job as a welder, and her mother, Mang, stayed at home with Vang and and her five younger siblings. Nobody spoke English, so Vang taught herself by watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood on PBS. Then, she taught her family.

Annie with her father, Seng Fong, and her mother, Mang, in front of a church at the Ban Vinai refugee camp in Thailand in 1976.COURTESY ANNIE VANG

The Hmong have a long history of oral speech, but for centuries there was no written language, apart from imagery that appeared on traditional tapestries Vang translates in Hmong as “paaj ntaub.” That changed in the 1950s when William Smalley, an American linguist, reportedly set out to help Hmong people in Laos develop a permanent writing system, which is now used all over the world.

Vang says that because many Hmong people did not learn to read or write in their own language before coming to the U.S., her native Hmong dialect is in danger of disappearing. “A lot of our rich cultural history and stories are lost, because they were not written down or recorded,” she says. “We as a Hmong people have lost so much in our journey searching for freedom.”

The best way to ensure it isn’t forgotten, she came to realize, was to digitally document the language—and encourage younger people to learn to speak it too.

After some of Vang’s friends asked her how to say basic phrases like “hello” and “goodbye” in Hmong, she decided to create a Hmong-English language app. “There were no online resources for Hmong audio phrases, so I decided to write a list of commonly used phrases and recorded all the audio content myself,” she says.

In 2011, those recordings became the first iteration of HmongPhrases, an app that allows users to search for a phrase in Hmong, play a sound of how to pronounce that phrase, and then practice saying it out loud. “My goal is to leave a digital footprint of our Hmong language for future generations,” Vang says.

Annie (left) with her sister, Song, in traditional Hmong clothing at a Hmong New Year’s celebration in Fresno, California, in 1993.COURTESY ANNIE VANG

Since then, HmongPhrases has been downloaded more than 2,000 times. Last January, Vang re-recorded all new audio content, and added new features to the app, which caters to students, teachers, and non-native speakers so that they can have conversations with their Hmong friends. She has uploaded 3,000 translations and created flashcards to help users memorize phrases.

In July, Vang attended Apple’s Entrepreneur Camp, an immersive lab that offers female entrepreneurs guidance on their apps and mentorship from top tech experts, to further develop the app.

By adding more words to HmongPhrases, Vang hopes to ultimately save a language that has traditionally only been spoken within tight-knit communities. “Our language bridges the gaps of communication from the young and the old, so that we can communicate and share stories,” she says.