The New Yorker Loves to Put Black Women on Its Covers. But Black Women Still Don’t Draw Them, Why not? This year, for the first time in the character’s near centurylong history, Tilley has been rendered as a black woman.

It’s Black History Month, and you know what that means: time to celebrate the bloodless heritage of a legacy media property. On Monday, the New Yorker trotted out old Eustace Tilley, its monocle-wearing mascot, for the magazine’s annual anniversary issue.

It’s Black History Month, and you know what that means: time to celebrate the bloodless heritage of a legacy media property. On Monday, the New Yorker trotted out old Eustace Tilley, its monocle-wearing mascot, for the magazine’s annual anniversary issue.

It’s a lovely cover, all kidding aside. But it exists within the larger context of a profound lack of diversity in the stable of artists that Françoise Mouly draws upon in her role as the magazine’s art director.

My question is more basic, and more broad: How many, if any, black women have ever drawn a New Yorker cover? To be clear, I don’t doubt that the cover’s artist, Malika Favre (whose mother is French Algerian), is “allowed” to draw black women. Of course she is.

The answer is zero, at least for the past 15 months. With the caveat that Google is an imperfect tool for mining the demographic data of total strangers, let me offer a few statistics. Since the 2016 election, the New Yorker has published 60 covers, fully half of which were drawn by white men who are 55 or older. Of the 34 artists whose work was featured during that time, only two were black—and both of them were men.

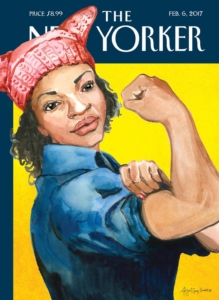

But the covers themselves represented black womanhood with some frequency, often as a political signifier. Take, for instance, the magazine’s February 2017 cover about the women’s march, which reimagines Rosie the Riveter as a black woman in a pink pussy hat. The white artist, Abigail Gray Swartz, crowed about the cover as a gesture of inclusivity, but I’m not so sure. A white woman hiring another white woman to draw a black woman (in what was destined to become one of the most widely disseminated images of the march) and calling that intersectionality—well, that contains a very different, and much more difficult, sort of message about the “movement” that perhaps doesn’t lend itself so well to pat cartoons. Even as that cover ran, Mouly garnered widespread praise for publishing the work of (unpaid) artists, including many women of color, in Resist!, the political zine she curated with her daughter, Nadja Spiegelman.

But the covers themselves represented black womanhood with some frequency, often as a political signifier. Take, for instance, the magazine’s February 2017 cover about the women’s march, which reimagines Rosie the Riveter as a black woman in a pink pussy hat. The white artist, Abigail Gray Swartz, crowed about the cover as a gesture of inclusivity, but I’m not so sure. A white woman hiring another white woman to draw a black woman (in what was destined to become one of the most widely disseminated images of the march) and calling that intersectionality—well, that contains a very different, and much more difficult, sort of message about the “movement” that perhaps doesn’t lend itself so well to pat cartoons. Even as that cover ran, Mouly garnered widespread praise for publishing the work of (unpaid) artists, including many women of color, in Resist!, the political zine she curated with her daughter, Nadja Spiegelman.

New Yorker covers are rapidly losing any cultural cachet they once had, with the occasional transcendent image by, say, Maira Kalman, Ivan Brunetti, or Malika Favre getting lost in all these glorified greeting cards and hackneyed, incoherent political cartoons that have become the status quo. It’s easy to buy into the fiction that diversity doesn’t matter much in such a silly, square corner of the art world. But as Mouly herself has noted, New Yorker covers are “the best-paid job” in editorial illustration. Representation matters, and maybe those dollars matter most of all.

Read more on slate.com.