By Megan Janetsky

During Colombia’s more than half-century armed conflict, bloodshed between left-wing guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries and the country’s military forced nearly eight million people to flee their homes.

Women and Afro-Colombians, in particular, faced greater levels of violence in the conflict and would often arrive in far-off cities with nothing and no-one.

In an impoverished neighborhood in the sweltering coastal city of Cartagena, a group of displaced women decided to do something about it.

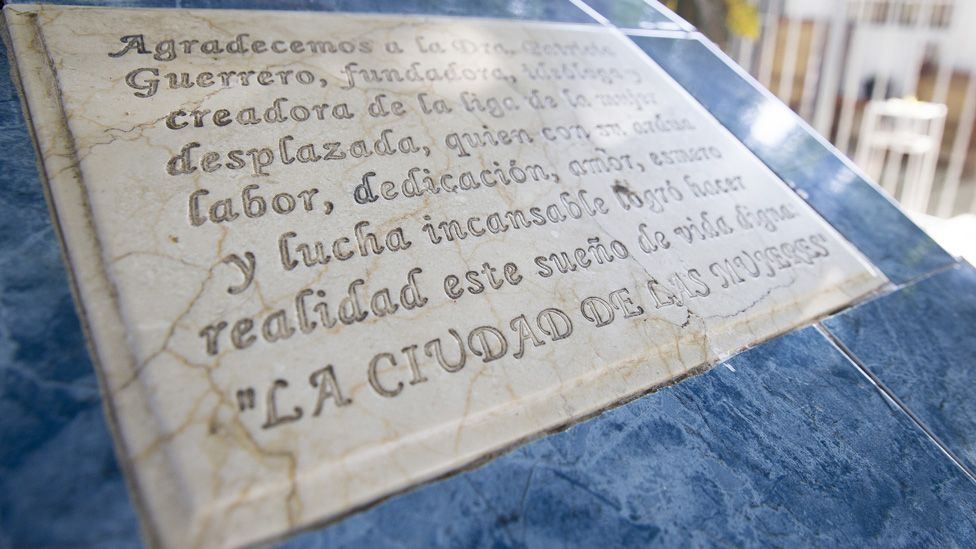

They formed the League of Displaced Women and in 2003 began to construct their own community brick by brick: The City of Women.

The City, in the nearby municipality of Turbaco, is made up of 100 houses the women built with their own hands.

During Colombia’s armed conflict, sexual violence and targeting of women were used to sow fear. Many of the women in the City are survivors of that violence.

It offers refuge to the women and their families who faced killings, rapes, threats, and other violence both in their homes and during their displacement. All of the crimes against them remain in impunity.

That struggle has pushed them together and given them the power to push back against things like machismo, societal norms, and stigmas against displaced people still prominent in much of the country.

“The war had taken our homes from us, it cut you from your customs, your dreams, your land.”

Consuelo Villega Mendoza, 44, is from a town in the northern region of Sucre and was forced to flee after paramilitaries began massacring communities near her home.

“It was only a matter of time until it happens to you,” she said. “I left out of fear.”

With her daughter, she runs a restaurant out of the home she built. They are preparing mondongo, a Colombian soup.

“Being a part of the League of Displaced Women has helped me a lot because they have taught me how to move on. “

Women in the City have fought to get justice for the crimes committed against them, but all 159 cases of gender-based violence and displacement remain unresolved.

Alneris Orozco Caupo, 47, poses for a portrait in a mirror in her home in the City of Women. Originally from the north-western region of Cesar, she was forced to flee with her two young children more than 20 years ago due to the territorial conflict between paramilitaries and Farc rebels.

She proudly displays photos of her children graduating from high school and university, something she was never able to achieve due to the violence.

Before she was forcibly displaced, she used to weave large traditional Colombian sombreros, but the plants from her home in Cordoba do not exist in the dry plains near Turbaco, so she does her best to weave and sell the small ones.

Erika Maria Gamarra Caro, 42, is from El Carmen de Bolívar and fled to Cartagena after members of her family were murdered during massacres carried out by right-wing paramilitaries as they fought left-wing Farc rebels.

She says that she was repeatedly sexually assaulted during her displacement but the League has helped her to recover.

“I realized I was a woman and that I had rights, and I began to demand them,” she said. “Now, I’m not a shy woman, I’m not a woman unable to speak because of fear or the feeling that as a woman I’m not worth anything.”

While building the homes, members of their community were killed, raped and threatened, but they say their finished city stands as a symbol of peaceful resistance.

Carmen Beluas, 45, fled from her home in Copey in the late 1990s after her husband was murdered by paramilitary forces who accused them of being affiliated with the guerrillas.

She left with her three children and arrived in Cartagena without knowing anyone. She says she will always remember how her husband was taken from her.

“It’s something that will never go back to normal. I know I have my children, but there are still things I’ll never forget.”

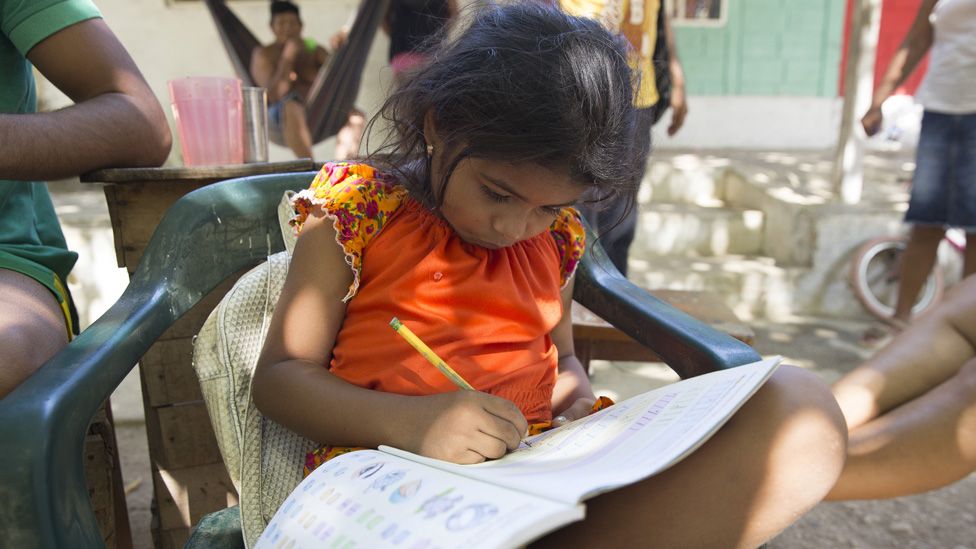

Despite its name, the City of Women also has male residents. The women, often heads of households, created the city for their children and partners to live in and the community has grown as members started having their own families in the City of Women.

The community is completely self-sufficient and has its own school, stores, restaurants and community center for children like Shayla.

Eidavis Montes and fellow community leader Lubis Cardenas say the City has changed women’s roles and outlook on life.

“Oftentimes women in the countryside are timid, they care for the children, tend to their husbands. If you don’t know anything else you’re always going to be in that role,” Eidavis Montes says.

“This life we have created has taught me that I am a woman with rights, that we can do other things.”

As Colombia struggles to emerge from more than a half-century of armed conflict, the women in the city plan to tell their stories and seek justice before the country’s transitional court system.