Women’s Mental Health Care in Prison

The continued lack of mental, emotional, and social health programming for women in prison during the COVID-19 pandemic may actually cause the virus’s most devastating and long-lasting health effects for this population.

By Emma Athena

Until September 2021, 33-year-old Cheyanne Tanner was incarcerated at Florida’s Homestead Correctional Institution, a state prison on the southernmost edge of the United States, some 30 miles south of Miami, abutting an alligator farm. During her time there, it held more than 600 women inside, crowded together, 70 to a room.

Having struggled with drug addiction in the past, Tanner enrolled in a substance-abuse prevention program provided by the prison in 2019, but found it to be largely ineffective. And once COVID-19 hit in 2020, a prison-specific “new normal” unfolded fast: spreading sickness, total lockdown, no more time outside, no visitors, no mail, fewer phone calls, less movement around the prison, no group classes, therapies, or programming—all of this led to a relapse for Tanner.

“There were quite a few women in there who ended up relapsing like I did,” she says; not even enhanced pandemic-lockdowns could keep drugs from circulating in the cells. “We got high to numb the pain,” she says. And with COVID, the pain of prison life was intensifying.

“But,” Tanner clarifies, “that was before I was involved in the LEAP program.”

LEAP stands for Ladies Empowerment and Action Program, and is a nonprofit re-entry program run by Miami-based community members who organize in-person classes and group therapies for women in prison, helping them build employability and essential life skills through entrepreneurship, self-love, and mentorship. LEAP helps women navigate the release process—finding housing, transportation, employment, and other forms of assistance on the outside. It’s the only community-based organization (CBO) in the Sunshine State to provide women in prison with gender-specific, holistic support.

The program is designed for women in the final six months of their incarceration, so Tanner had to wait until the spring of 2021 to participate. LEAP was a possibility for her because Homestead created “cohorts,” or groups of women who shared cells or dorms that could visit communal areas and participate in activities together following the most intense lockdowns. This allowed staff to quarantine certain groups of people instead of the entire prison all at once.

Having hands-on support from local community members made all the difference. “Being able to do exercises and writing assignments in areas of pain and trauma helped me a lot,” Tanner explains. “I have since been able to forgive myself and forgive others for things that I’ve been through and things that I’ve done, and that is a big part of remaining sober. Doing the trauma and addiction counseling through LEAP changed my life.”

Incarcerated women respond more successfully than men to rehabilitative treatments.

Women represent less than 10 percent of the country’s incarcerated population, but they’re more likely than men to suffer from co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders, according to Holly Ventura Miller, PhD, a professor and graduate program director at the University of North Florida’s Criminology and Criminal Justice Department.

These compounding factors put women at the highest risk for relapse and recidivism (returning to prison); it also, however, makes them ideal candidates for receiving in-prison mental health care and social support. This assistance is especially critical given the fact that women enter and exit prison with challenges most men don’t have (e.g., higher rates of sexual or domestic violence and PTSD, plus most incarcerated women have two or more children, like Tanner, and are their primary caregivers). And it works. When women participate in supportive groups and re-entry programming, they’re less likely than men to recidivate, per a 2021 report for the U.S. Department of Justice. The most effective programs, says Miller, who has studied how women re-enter their communities after incarceration for more than 20 years, are ones that bridge the gap between the institution and the outside community and address the multifaceted challenges women face, like CBOs.

LEAP is one of the hundreds of CBOs supporting people incarcerated in the U.S. in a holistic way.

CBOs and their offerings can take many forms: higher education courses, entrepreneurship classes, theater workshops, group therapies, substance abuse support, conflict resolution education, transitional housing support upon release. Really, they can be “any kind of program run by the community that reinforces the inherent worth and dignity of people who are incarcerated,” says Caitlin Dunklee, organizing director of the Transformative In-Prison Workgroup (TPW), a coalition of more than 85 CBOs in California and New York that offer trauma-informed, community-based, in-prison healing programs. CBOs are typically composed of small teams of people privy to local challenges, and are primarily funded by grants or crowdsourced monies rather than state or federal funds.

Since Tanner’s completion of the LEAP program and her release in 2021, she’s stayed sober, started working at Dragonfly, the boutique thrift store that LEAP runs in Miami, and started her own business. From every LEAP class, “I learned something,” Tanner says. “I learned that I have skills that I didn’t know I had. I learned how to be able to share my past experience—because when you do go for an interview, they ask about your criminal history. I learned how to be able to talk about that, and also mention the things that I have done to change.”

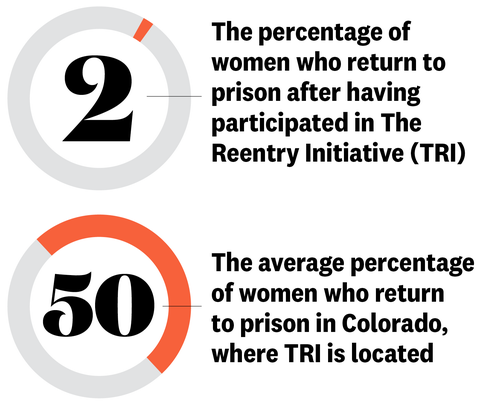

Tanner is far from the only CBO success story. Recidivism rates among CBO program participants are regularly reported in the single digits, whereas average recidivism rates in states like Colorado and California hover around 50 percent.

Support for and access to CBOs were already lacking, and the pandemic amplified those issues.

Genea Richardson spent 18 years in the California prison system, and only during the final years of her incarceration was she eligible to participate in CBO groups (many women are never able to get access, particularly if they’re not up for release). Only in those last few years of her time in prison did she feel like forward progress was possible. “They actually gave me tools,” she says, “tools that I can use.”

Their rehabilitative value aside, CBO groups became critical sources of refuge during Richardson’s time in prison. “They became a safe space in a dark place for us to examine our souls—to pull our souls out of our body and look and to try to obtain some type of healing and some type of understanding,” she says.

While partaking in various educational and therapeutic CBO programs—like Freedom to Choose, which escorts students from diverse cultural backgrounds into prisons to participate in communication workshops—Richardson learned about other ways of life and practiced and honed listening and anger management skills while building her self-esteem. Richardson eventually became a group facilitator herself, leading a peer-to-peer workshop called “Girlfriend What Happened?”.

Things had been looking up for Richardson as 2020 rounded the corner; she felt her summertime release couldn’t come quickly enough. But COVID arrived that spring, and for several rounds of lockdowns, Richardson and other incarcerated folks across the nation reported being inside their cells for weeks at a time, comparing the conditions to solitary confinement. “It was a time of despair,” Richardson says. “I mean, we’re already in a state of despair, but that created great despair.”

The shuttering of social programming during that time compounded the mental health issues women were facing. In the ensuing two years, access to programming has struggled to get back to pre-pandemic levels, says Dunklee. CBOs have always had to fight to secure funding and access, and now, the situation is dire.

There have been pockets of time when visitors and organizers “can go back in for a minute, but then there’s another shutdown,” Dunklee says. It’s completely stalled the in-prison workshops given by TPW’s collective of program providers. Virtual and correspondence adaptations haven’t been successful due to equipment and staffing shortages, because, despite the documented success of CBOs, they get less than a tenth of one percent of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s 14.2 billion dollar budget.

Reduced CBO programming is driving up rates of depression and anxiety among incarcerated women.

Isolation has negatively impacted many facets of mental health for women in prison, says forensic psychiatrist Ayesha Ashai, MD, clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. Dr. Ashai provides treatment for local incarcerated folks and formerly-incarcerated people who struggle with mental illness as part of a therapeutic intervention program. “With COVID, the biggest issue is that we have such an onslaught of people being restricted to their cells, not being able to attend any of these mental health appointments or therapeutic programs,” she says.

Those who are experiencing the trauma of incarceration need access to people they can relate to and who understand what they’ve been through, says Dr. Ashai. “To not have that support, to not have an outlet, is extremely detrimental toward their mental health. They really feel like they’re getting the worst of the worst care, and that no one cares about them.

The Reentry Initiative (TRI), is one CBO that, pre-pandemic, provided incarcerated women with extra mental health support in the eight months leading up to their release, as well as reintegration opportunities upon their return to their community in Colorado. In 2020, when they were no longer able to enter prisons to provide therapies, TRI pivoted exclusively to transitional, post-release support, and was only able to reenter prisons and reestablish their in-prison programming in March 2022.

COVID lockdowns have driven “a lot of depression, tons of anxiety” among the incarcerated women that TRI works with, says Emily Kleeman, the executive director of TRI. “You’re already cut off as someone who’s in prison, and to watch the mental health conditions continue deteriorating inside, it breaks your heart.”

Unfortunately, it’s hard to say how long they’ll be able to keep up their current in-person programming with COVID still a threat—each facility makes lockdown decisions based on guidance from the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), the law enforcement agency responsible for the “care, custody, and control” of incarcerated individuals, in accordance with the CDC. The BOP’s Modified Operations Plan is based on the facilities’ COVID-19 medical isolation rate, the vaccination status of staff and those incarcerated, and their respective community transmission rates, which fluctuate seasonally.

But COVID precautions haven’t necessarily kept women in prison safe.

Despite the strict lockdowns and program eliminations, COVID has infected incarcerated people in the U.S. at rates far higher than the country’s general population, reports the University of North Carolina’s COVID Prison Project. In fact, incarcerated people are more than three times as likely to contract COVID than a member of the general population in the U.S. A majority of the nation’s largest, single-site outbreaks have been in jails and prisons too.

The inability to socially distance is one of many ways that the pandemic has challenged state corrections systems, says Annie Skinner, spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Corrections, noting that they’ve been working consistently with public health officials and their medical staff to make decisions about lockdowns on a facility-by-facility basis. “We want to be doing programming, we want to be having people from the outside, we want to be having visitation,” she says. “That’s important to us. And at the same time, the challenge with this pandemic has been balancing that desire to have these great programs…with the risks associated to the incarcerated population.”

One way to overcome those risks is by providing prison-run programs (like the substance-abuse group Tanner was a part of prior to LEAP). But these programs differ from CBOs in a significant way: They’re run by people who work in and for the prison system, instead of community members from outside. Having support programs that are led by people from the community, not officers, is crucial, says Dunklee, “because you can’t really get healing from the same person who’s incarcerating you.”

Adequate care, both physical and mental, is a constitutional right while in prison, says Dr. Ashai.

From Tanner’s perspective, the lockdowns and ensuing deterioration of incarcerated folks’ mental states have only highlighted the importance of and need for more community connection and support in prisons, especially as the world moves forward with and beyond the virus. As an incarcerated individual, you had to be lucky to get into one of these limited CBO programs before the pandemic. Now it’s even more unlikely.

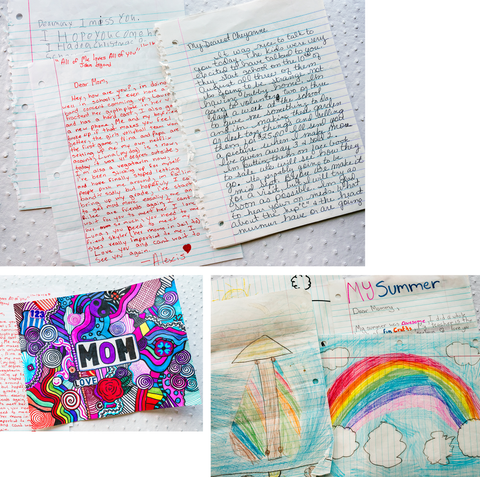

Skinner from the Colorado Department of Corrections says that they, like Homestead, have found some success in cohorting, or grouping women who share dorms to quarantine and participate in activities together. To some degree, adapting some programs to be virtual or conducted through the mail has allowed threads of connection to remain.

But without continued access to quality programs, neither Tanner nor Richardson put much faith in the system. “Now we’re going to be citizens returning to society, and so, if there are no tools for us to obtain healing, to find a better way to do things, or just to create an understanding, then how are we going to come out as healthy citizens?” Richardson says.

Increasing CBO funding and program access would have a real, lasting impact on incarcerated women.

Within two days of her release from Homestead, Tanner began working full-time at Dragonfly. Now about nine months out of prison, “I am a workaholic,” she says. “I’m so busy and I try to stay as busy as possible. I have to pay $510 a month in child support.” Plus, along with active recovery habits, having a full schedule helps her stay sober.

While working for LEAP, she’s also been building her own mobile car detailing business: The Grime Unit. If it wasn’t for an entrepreneurial class that LEAP hosted during her time at Homestead, “this business would not even have come about,” she says.

And to this day, Tanner says the folks behind LEAP “are my biggest supporters. And they have my back, and they root for me, and it feels good to know that I have these amazing people who aren’t related to me who are fighting for me.”

Overall, Tanner’s success boils down to “the fact that LEAP cared—the fact that they didn’t judge us,” she says.

In other words: Tanner finally found true community, and a stable place to assimilate her past and present as an individual. She’d been given a chance to walk a bridge between those inside and outside of prison.

Image: Erika Larsen